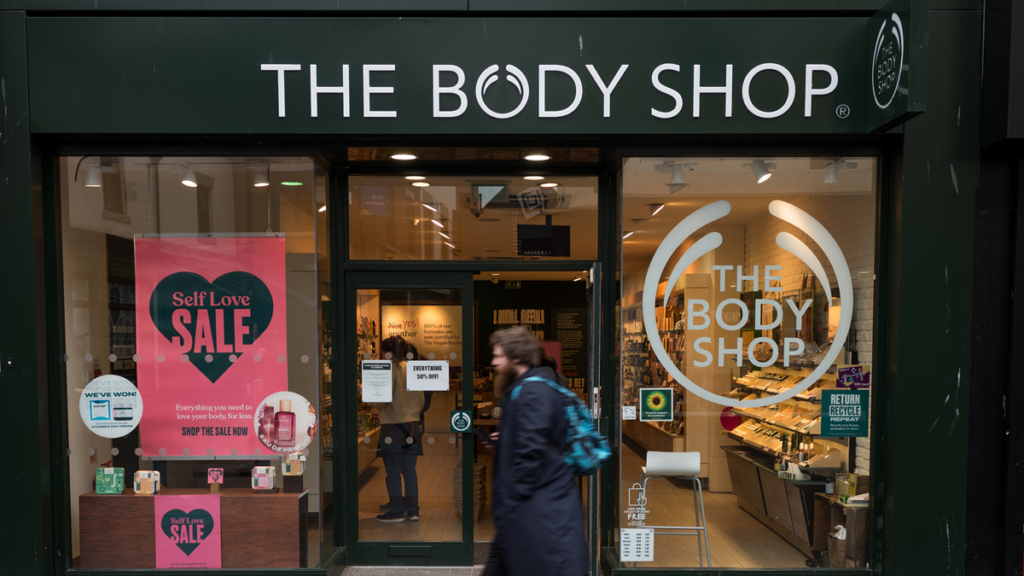

What went wrong at The Body Shop – and what can we learn from it?

The Body Shop lost relevance with its core customers, while successive ownership and leadership changes confused the strategy

The story of The Body Shop has never lacked for twists and turns. It was founded by an activist entrepreneur, Anita Roddick, who disliked the cosmetics industry and the business status quo in equal measure. Yet from one shop in a Brighton side street, The Body Shop blossomed into an international company selling ethical products in a sector that often embodies all the worst aspects of capitalist indulgence.

Roddick inspired a generation of entrepreneurs – many of them women – who put people before profit. Then, a year before her death in 2007 at only 64, Roddick puzzlingly sold the business to one of the beauty care giants she had so reviled, L’Oréal. After a decade the French firm sold it to a Brazilian cosmetics brand, Natura, which in turn sold it to a private equity firm, Aurelius, which owned it when it went into administration in February.

The Body Shop’s early success

Roddick, who opened that first shop in Brighton in 1976 while her husband Gordon was riding a horse from Buenos Aires to New York, admitted in her autobiography she knew nothing about business when she started. “I had to learn a lot,” she wrote. “My passionate belief is that business can be fun, it can be conducted with love and [it can be] a powerful force for good.”

To fund expansion, she sold half the business to a friend’s boyfriend for £4,000 after the bank refused her a loan to open a second shop. When The Body Shop went public in 1984, the stake was valued at £4m; by 1992, when Roddick wrote her autobiography, it was worth in excess of £140m. She never begrudged him his good fortune.

Her pioneering spirit and emphasis on ethical business practices set Roddick apart from other businesses. “They thought it was not the business of business to get involved in wider issues, in the protection of the environment or involvement with the community; I thought there was nothing more important,” she wrote.

For those born before 1990, memories of the iconic cucumber cleanser, shea body butter and kiwi fruit lip balm linger. Shop shelves were filled with products smelling of apple, dewberry and grapefruit, captivating consumers with their distinct scents. The environmentally friendly ideas were ahead of their time and Roddick’s green cosmetics store was a success from the beginning.

My passionate belief is that business can be fun, it can be conducted with love and it can be a powerful force for good

Anita Roddick, founder, The Body Shop

Competitors followed in Roddick’s wake. Lush, established by Mark and Mo Constantine in 1995, has expanded to more than 880 stores in 48 countries. Sharing with Roddick a commitment to cruelty-free cosmetics, Mark Constantine told The Times that she was “intuitive” and “knew what customers wanted”.

He hit it off with Roddick when they met in his 20s and he worked with her to produce cocoa butter body cream. He told The Guardian he had been “inspired and terrified” by her combination of iron principles and whip-smart business acumen.

“She did things that nobody else had the nerve and the balls to do. I don’t think B Corps would exist without The Body Shop,” he said.

Becky Willan was environmental manager at The Body Shop from 2006 to 2008. She sees the firm as a “pioneer in ethical consumerism” that was “committed to an activist stance from the start”. Its pioneering spirit went beyond the environment, she said. It was one of the first firms to do CV-less hiring, she says, and had a lasting, dedicated commitment to change.

“Businesses need to be bold and brave; they need to own their mistakes and they must play the long game,” she said.

The Body Shop’s sale to L’Oréal

Roddick’s pledge to “stay quirky, keep raising eyebrows in the business world and err on the side of eccentricity” meant that the sale to L’Oréal for £652 million in 2006 came as a shock. Her promise to “compromise on almost anything except The Body Shop’s values, aesthetics, idealism or sense of curiosity” was called in to question.

Even though L’Oréal was known to test on animals, Roddick surprisingly found common ground with the French cosmetics giant. At a press conference, she described feeling “flattered and seduced” by the sale, saying that “for both Gordon and I, this is without doubt the best 30th anniversary gift The Body Shop could have received.”

In some ways, she was right. Under L’Oréal’s ownership and with Peter Saunders as acting chief executive, The Body Shop expanded rapidly, with 2,400 stores across 61 countries by 2007. However, according to YouGov’s BrandIndex, which monitors public perception of consumer brands, satisfaction with The Body Shop plummeted by nearly half after the acquisition.

Mark Constantine sees the company’s decision to move production to the Philippines as a pivotal moment. It coincided with a marketing strategy focused on discounting to boost sales, which became the only message customers heard.

“You can’t cheapen everything, remove the values and take more profit without the customers noticing and going elsewhere,” he said in The Times. “Modern business is brutal and ethical brands rely as much on what they won’t do as what they will.”

The “strange” case of administration

A decade later, David Boynton, chief executive of The Body Shop from 2017 to 2023, navigated a challenging period marked by the acquisition by Brazil’s Natura & Co. The company seemed a more natural fit for The Body Shop but the new owners took time to understand the European market and were struggling to fund the investment The Body Shop needed amid rising interest rates.

Citing a need to “refocus operations”, Natura sold the company to the private equity firm Aurelius Group in a deal worth £207 million in 2023.

Boynton admits that the resulting “insolvency seems a little strange to most onlookers” because most of the business’s UK stores were profitable. However, Boynton says problems during his tenure including the need to deal with loss-making stores in continental Europe and the US significantly impacted overall performance.

“This was certainly the most difficult challenge my team had to contend with,” he says.

You can’t cheapen everything, remove the values and take more profit without the customers noticing and going elsewhere.

Mark Constantine, founder, Lush

Adding to these issues, the high street today is different. It bears the scars of Covid-19, its shuttered shops symptomatic of the struggle to survive. Against the backdrop of a cost-of-living crisis, the high street is a symbol of economic strain. But Boynton says the administration of The Body Shop is not a story of a failing brand or a failing high street. If The Body Shop can’t point the finger at the economy for its problems, what is to blame?

What we can learn from The Body Shop’s collapse

Professor Adrian Palmer, head of marketing and reputation at Henley Business School, sees parallels with the ‘wheel of retailing’, a theory that outlines the evolutionary process of retail businesses in which initial enthusiasm often gives way to complacency.

At The Body Shop, this ultimately caused it to lose relevance among crucial market segments. Those customers who grew up with The Body Shop “no longer see its values as distinctive” and once innovative products “have now become commonplace,” he says.

Successive ownership and leadership changes also played a role. The Body Shop has had three different owners since Roddick sold to L’Oréal. “Each change of ownership structure signalled different approaches to strategy, which resulted in confused and changing market positioning,” says Palmer.

Amid these shifts, The Body Shop encountered an increase in copycat brands, undermining its ability to maintain its distinctive market position despite its strong USP, as noted by retail analyst Richard Hyman. It also needed investment at a time when its owners weren’t prepared to sink more money in.

“An additional issue is that the business was successively acquired by big businesses that paid too much. This made the owners less willing and able to invest in the business,” Hyman says.

The Body Shop is now closing 75 stores in the UK. MPs, meanwhile, are calling for a review of what led to its downfall amid allegations that millions of pounds were withdrawn from the company before its collapse.

Roddick’s approach shows that the pursuit of maximum profit doesn’t need to dictate every decision. But when a company veers away from its ethical roots it puts its brand at risk, particularly in a competitive market. These missteps serve as a reminder that reputation and trust, once tarnished, can be challenging to regain.

When Roddick started The Body Shop, she described her hope that the cosmetic industry would realise that the threat it posed was not economic but “the threat of being a good example”. Unfortunately, it stopped being both.

Timeline of The Body Shop

1976 Anita Roddick opens first The Body Shop store in Brighton.

1978 The Body Shop begins franchising stores across the UK.

1980 Opens first overseas store in Brussels.

1984 Floats on London’s Unlisted Securities Market.

1989 Establishes The Body Shop Foundation to support environmental and social causes.

1990 Opens 500th store.

1994 Launches ‘Against Animal Testing’ campaign.

1998 Roddick steps down as chief executive.

2006 Roddick sells to L’Oréal in £652 million deal.

2007 Roddick dies, leaving £51 million fortune to charity.

2017 L’Oréal sells The Body Shop to Brazil’s Natura & Co for £880 million.

2023 Natura sells to private equity firm Aurelius for £207 million.

2024 Aurelius puts The Body Shop’s UK division into administration. It also files for bankruptcy in markets including the US, Canada, Germany and Belgium.